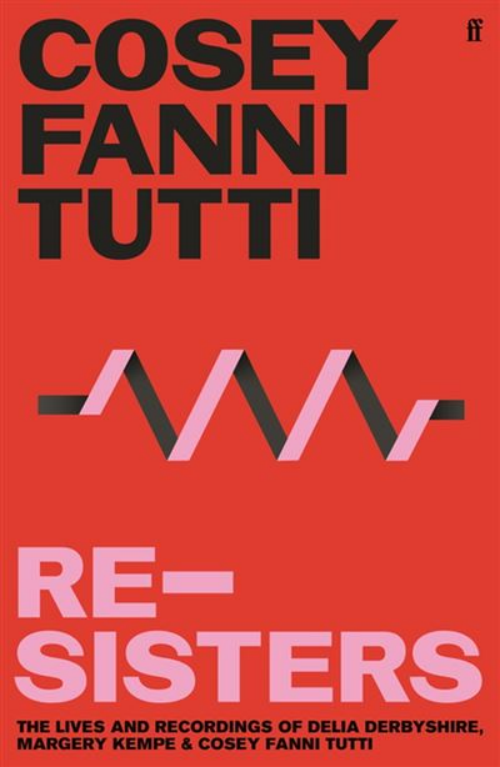

Cosey Fanni Tutti is likely best known to readers of Freq as a musician of some reknown, part of the imperative of Throbbing Gristle and with a substantial discography (Chris and Cosey etc). Art mavens know her variously for her work in pornography and mail art (also etc). As of 2017, she’s found a new life as the kind of writer who gets featured on Woman’s Hour on Radio 4.

Cosey Fanni Tutti is likely best known to readers of Freq as a musician of some reknown, part of the imperative of Throbbing Gristle and with a substantial discography (Chris and Cosey etc). Art mavens know her variously for her work in pornography and mail art (also etc). As of 2017, she’s found a new life as the kind of writer who gets featured on Woman’s Hour on Radio 4.

It’s great news, genuinely, that Faber have retained her to write Re-Sisters – subtitled The Lives and Recordings of Delia Derbyshire, Margery Kempe and Cosey Fanni Tutti. One of those figures likely known to Freq regulars for her substantial contribution to early electronic music; the other is probably lesser known (although there’s plenty of incorrigible occultists in their ranks, so who knows?)

So what we have here is a book that could’ve been several books — a biography, a hagiography, an academic study, a treatise on sexism across the ages. The fact that it’s all of these and none is a testament to Tutti’s astonishing affection and empathy for her subjects. Delia Derbyshire and Margery Kempe both are known primarily for being women who operated in atypical areas, but Tutti’s gift here — and it’s a gift wrought from personal experience — is in recognising what they did, not that they did it despite difficulties.Kempe meanwhile, is perhaps best known for being probably the writer of the first English autobiography. Tutti doesn’t delve into the historiography of this (doubtless as it’s well covered elsewhere), but rather brings to life the woman behind the words. A woman who suffered terribly in many ways and was constantly belittled and threatened, often mortally, and nevertheless pressed on with her epiphanic belief in her own chastity and following a pilgrim’s path.

Probably the most effective turn of this book is that Tutti doesn’t dwell extensively on one or other of her subjects — we get a bit of Derbyshire, a bit of Kempe, and all woven into a fabric that frequently relies upon weaving both women’s experiences into Tutti’s. That’s not to say Tutti vainly compares herself, but rather builds from hers and other women’s experiences to illustrate an aspect of one or the other’s life.I don’t want to give away too many details here, but if you’d ever wondered about Derbyshire’s sexual proclivities or housing situations, it’s all here. Possibly my favourite revelation is that her preferred snooker player was Alex Higgins. Tutti’s compassionate writing extends to sticking the boot in to the Tories — which was by no means necessary, except insofar as it’s always worth having a pop at those venal shitlords.

Possibly the greatest achievement of this book — I’m pretty sure a biography on an important composer of electronic music would likely be only marginally more popular than a biography of a fifteenth-century religious woman. The fact that I can well imagine this book appealing far beyond that remit, and in fact the remit of “people interested in Cosey Fanni Tutti”, is probably the heartiest recommendation I can imagine. Shout out Ms Tutti.-Kev Nickells-