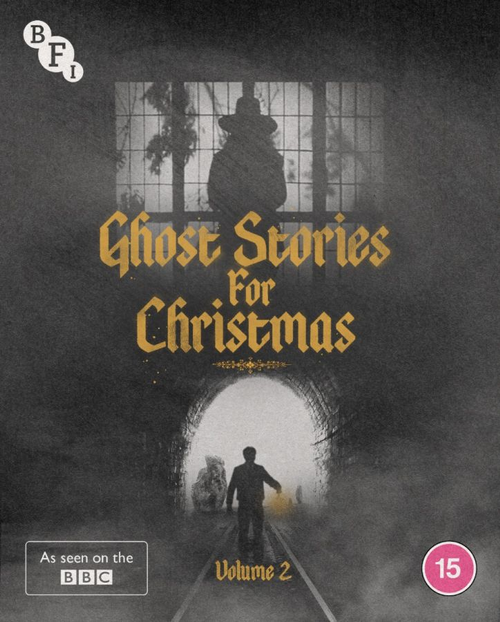

One of the great lost traditions of British television, the BBC’s Ghost Stories For Christmas ran through the seventies and remain fondly remembered, a singularly British reading of classic horror stories.

One of the great lost traditions of British television, the BBC’s Ghost Stories For Christmas ran through the seventies and remain fondly remembered, a singularly British reading of classic horror stories.

The BFI’s first blu-ray reissue released last year consisted of the early and most famous entries, as well as the honorary entry of Jonathan Miller’s Whistle And I’ll Come To You, a more perfect standalone hour of television you’d be hard pushed to find. Volume 2 is a more varied affair, both in terms of content and quality, but what they hold is some of the most affecting TV horror of that decade, bringing to blu-ray for the first time the latter phase of a strand that remains essential viewing for any enthusiast of British macabre.

The Treasure Of Abbot Thomas is the first of the package’s films, and in many ways is the perfect opener as it is totally emblematic of what the initial run of the series was about, almost to the point of parody. Another MR James adaptation, another mystery unveiling horrors hovering from the past, another protagonist who is, in the words of Alex Davidson in the releases’s accompanying booklet, “academic, cynical and arrogant”. It works tremendously well as an introduction given the experimentation that will come later in the collection, a good baseline to show how much the series changes in its final iterations.The story concerns the Reverend Justin Somerton and his protégé, Lord Dattering, whom we meet exposing a huckster medium in a terrific séance scene. Somerton explains his researches on the local monastery, which holds tale of the titular treasure being hidden by a monk who was, according to legend, carried off by the Devil. The two then set off on an almost Holmesian adventure to follow clues to the treasure’s location. It’s the sort of thing that could be wildly overwrought; but, through James’s tone of fusty academia, it becomes completely believable.

A lot of this comes down to director Lawrence Gordon Clark who helmed the vast majority of the strand, as well as being its motivating force. He explained his primary philosophy that “television is not best suited to carry off big screen pyrotechnics”, and it is in this that his greatest gift is exposed. In holding this belief he is the perfect person to adapt James, both intently focussed in being as scary as possible whilst explaining and showing as little as he can.Instead, Clark makes sound absolutely paramount with the majority of the film’s most unsettling moments being sonic. It’s in the eerie soundtrack that resembles aggressive radiophonic birdsong, and the perfect foley work on a gurgling of slime, perhaps second only to the hacking cough in A Warning To The Curious in terms of evocatively terrifying noises conjured in this series. A magnificent work, worth getting the boxed set for alone.

The second film, The Ash Tree, is less successful. Still in the realm of the Jamesian horror of uncovered histories, the film abandons the academics and instead focuses on the aristocratic Sir Richard who, upon inheriting his family estate from an uncle, begins to be visited by strange visions concerning a witch trial some hundred years earlier. The script makes a valiant attempt to humanise the female characters in a manner that James never approached, but it is all a touch directionless, nothing like as drum-tight as the other adaptations, ultimately meandering to a slightly hollow conclusion.The film also contains Clark abandoning his principal of showing as little as possible for one of the all-time dreadful creatures. Not dreadful in the sense of terrifying, dreadful in the sense of so ludicrously and irredeemably stupid-looking that what atmosphere the film had is immediately pissed away in an instant. It’s the one moment you wish the immaculately done remaster wasn’t quite so successful, as it really shines a light on how utterly duff the creature truly is.

Their adaptation of Charles Dickens’s classic The Signalman is a whole different beast though, absolutely magnificent from beginning to end. It would wind up being the final period adaptation of the initial series and it’s a sublime way to go out, a perfect story for the strand faultlessly told. Its slim as anything plot, basically three conversations between an intrepid traveller and a lonely signalman, is rendered in extraordinary claustrophobic fashion. The location of the signal box itself is superbly indicative of this; a narrow valley that in its photographing seems to breathe with haunting loneliness and past horrors unable to be exorcised.Special mention must go to Denholm Elliot’s performance as the titular character. He’s the perfect actor for the series, recognisable but not a megastar, so he carries familiarity whilst also being kind of unknown. Every conversation between him and Bernard Lloyd as the traveller are crisp, tense and haunting, with both actors turning in immaculate performances of subtle, creeping dread. Elliot has this ability to colour the sinister with warmth and vice-versa, to bring these slight glimmers of sublime terror in amongst the mundane that set the films apart. It’s a truly wonderful thing.

Stigma is the shift that marked the beginning of the end for the series. Shifting to a contemporary setting of 1977, it does away with the frigid histories of James for the warped gentility of Penda’s Fen or Children Of The Stones (it particularly resembles the latter, given it was filmed in the same village).However this choice, rather than bold experimentation, was enforced. Clark explains in his never less than interesting introductions that he had wanted to adapt James’s Count Magus but the BBC couldn’t afford the rights, so he instead plumped for an original story instead. Said story is a pretty run of the mill example of the folk horror-adjacent plots of the era. A family move out to a cottage in the countryside which (quelle surprise) is the location of an ancient stone circle. They arrange to have the stones moved and in the process unlock an ancient curse that will have horrific consequences.

It’s a by no means original story, and the film has not been well thought of by many over the years. But, if you can see past Stigma abandoning most of what had been the strand’s defining hallmarks, there is an interesting work in there. Clive Exton’s script doesn’t have anything like the structural quality of James or Dickens, but instead it builds a loose nightmarish quality unlike little else of the era.It unfurls, treating time in a realistic fashion, more akin to an Alan Clarke film or a nightmarish episode of The Good Life than a ghost story. This gives the film an air of realism that brings real horror to its final stages, and a real visceral panic for the viewer. The film is a wonky, underrated gem that shows the value of such a collection; affording such films an opportunity to be re-introduced to a world now ready for it.

Alas, the final film in Volume 2, The Ice House, is a stinker. It’s another modern-day original story, but where the experimentation of Stigma had been forward-thinking and gently radical, the changes in style neuter what had been exciting and singular about what had come before.The story concerns Paul (John Stride) who, following divorce, has come to live at a residential health spa and begins to have suspicious feelings about those that run the establishment amid disappearances of guests and staff, and the mysterious ‘touch of the cools’ that is beginning to affect them. Now, you’ve probably already guessed the ending, and you’re right. This isn’t necessarily an issue; horror is in the telling the vast majority of the time. But it is the telling that is the problem.

Having seen Clark move to ITV, the series had lost its mastermind and key genius at its heart. There are sequences that you feel could have been terrifying in his hands but new director Derek Lister (fresh off of Corrie and Crown Court) is never more than workmanlike. You as a viewer are always fully aware you are no longer in the hands of someone who completely understands how to elasticate time, how to sculpt the frame so as to give the perfect hint of something, and to dredge such all-consuming terror from it.This marked the final instalment of the initial run. As the seventies became the eighties, Thatcherite materialism took hold and the slasher film came in, the supernatural faded from the peak of popularity. However, the boxed set also includes two later examples of the strand, revived in the mid-2000s: A View From The Hill and Number 13. Both of these James adaptations are flawed, largely due to being rather too slavish to the original series’ tone without the directorial flair that set those films apart, but they both have their moments. In fact, the whole first half of Number 13 is very well done, with the ensemble cast (including a young Tom Burke, already developing a skill for the cadish and scurrilous) absolutely nailing James’s tone of haughty self-important academia.

It’s a boxed set pumped full of extras for the devoted, including a heroically ripe Christopher Lee reading of Number 13 and a couple of enlightening commentaries from the likes of Kim Newman and Mark Gatiss, but it is the films themselves that are the key things here. At their best they are some of the most unique and perfectly executed single dramas of their era, whilst even the duffers remain worth the watch for their value in telling the story of the eerie on British television. Absolutely essential watching.-Joe Creely-