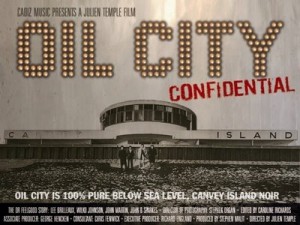

Although Julien Temple’s film about pub-rock heroes Dr Feelgood dates from 2009, it is only now receiving a DVD release (through Cadiz Music) in the US, and it’s this new edition that is reviewed here, although I’m not aware of any difference between this and the original release.

Although Julien Temple’s film about pub-rock heroes Dr Feelgood dates from 2009, it is only now receiving a DVD release (through Cadiz Music) in the US, and it’s this new edition that is reviewed here, although I’m not aware of any difference between this and the original release.

The film tells the story of the band from its origins in various Canvey jug and skiffle groups, in which the youthful Feelgoods-to-be played music that was already retro in 1970, but which could be profitably played to beachgoing holidaymakers from the East End, and which foreshadowed the Feelgoods’ later championing of stripped-down rock’n’roll, devoid of the fripperies and cod-mysticism of (some) prog rock – and Temple has dug a particularly choice clip out of the archives to illustrate the band’s lack of enthusiasm for prog. Elsewhere, he makes great play of the band’s moody, gangsterish image, splicing numerous clips from 1950s black-and-white British noir cinema into the film’s narrative, and linking the band’s reminiscences about driving from Canvey to London to play bone-rattling sets in heaving pubs with images of a gang of hoods on a smash-and-grab raid.

And the Feelgoods certainly carried an aura of menace – the rhythm section looked like heavy geezers, while Brilleaux and Johnson were something else. In the archive live footage, the singer appears to be a cauldron of barely-controlled lust and fury, brimming with danger and charisma. Wilko, meanwhile, was once memorably described as an “amphetamine-powered goblin”, and in the old clips we see him careening round the stage, all odd angles and nervous energy, firing razorwire riffs from his guitar in that unique choppy playing style. In the more recent interview footage, meanwhile, quite simply he steals the film.A true one-off, a former beatnik who studied English Literature at university (taking a course in Old Norse along the way), Wilko peppers his anecdotes and musings with quotes from Shakespeare and Piers Plowman, casts a sober eye over his own enthusiasm for the trappings of fame at the height of the group’s success (an archive interview is headlined, “Wilko: for fame and money I’d eat shit”… “I was insufferable”, the modern-day Wilko tells the camera) and discusses the rift between himself and Brilleaux that eventually led to his departure from the band, having written the great bulk of their material up to that point. All this is delivered in a bug-eyed, hyperkinetic style that is effortlessly charming, although it is easy to imagine him being a difficult person to be around, particularly when afflicted by speed-induced paranoia – as seems to have been the case at times to judge from descriptions here. Like his friend Lemmy, he and his bandmates had different drugs of choice – Wilko favoured speed and hash, eschewing alcohol altogether; the others drank the place dry wherever they went. These preferences only served to emphasise and magnify the tensions on both sides.

There are a few things to quibble over: the noir clip device is striking initially, but is then overused; and a few sequences feel oddly contrived, particularly those in which an associate of the band is shown relating his memories down the phone, hunching uncomfortably in a public phone box for no discernible reason. A more serious criticism might be made regarding the way the band’s songs are presented. The pared-down attack of their music often sees them referenced as precursors of punk (although interestingly none of the band or their inner circle seem particularly bothered about that claim here) and there are any number of brief clips showcasing their urgent, hard-edged, slightly-but-crucially-tweaked high-octane blues boogie and basic rock’n’roll. But it does seem odd that in a film about a rock band, we don’t get to see a single song performed in its entirety and I suspect most viewers will feel they could have lived without some of the more peripheral anecdotage in return for some full-length clips. But overall this is such an engaging, high-quality film that even this potentially fatal flaw feels like a fairly minor lapse.The film deals almost exclusively with the mid-’70s years of the original line-up; the post-Wilko period is telescoped into a few minutes at the end: there’s a brief interview with ‘Gypie’ Mayo, who replaced him, and a clip of the band playing “Milk and Alcohol” on Top Of The Pops. The fact that the band’s only hit single came after the ‘golden years’ is an interesting anomaly, but not one explored here, and the remainder of the band’s history (ever-changing, ever-touring line-ups under Brilleaux’s stewardship, until his sadly premature death in 1994, aged just 41) is mentioned only in passing. The fact of Brilleaux’s death, and the fleeting nature of the band’s short time at the eye of the storm, lend the film a valedictory quality, magnified now by the knowledge that earlier this year Wilko Johnson was diagnosed as terminally ill. But in the end, it’s the band’s raw energy and Wilko’s compellingly weird intelligence that are the lasting impressions left by this, perhaps the best film Temple has made. Anyone with even a passing interest in the band, or the development of ‘70s music, should see it.

-Haunted Shoreline-