Bernhard Wenger’s debut feature is a really strong first film, even if it never quite shakes off convention the way it would like. Matthias (Albrecht Schuch) is an actor. Sort of. He is, in effect, an actor for real life scenarios. Single but need a convincing boyfriend to get that couples-only flat? Hire Matthias. Need a pilot for a dad so you’ve got the most exciting parent at class career day? He’s right there.

Joe Creely

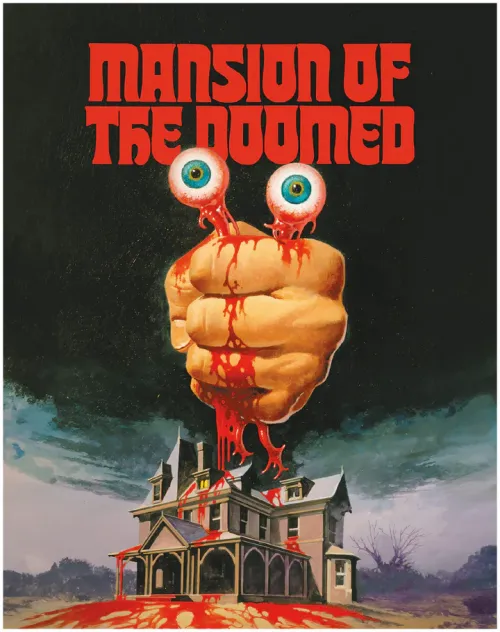

Initially conceived as a parody by feminist author and civil rights campaigner Rita Mae Brown, the film was ultimately financed by exploitation maestro Roger Corman, a man whose ‘bung some topless girls in it’ attitude to making his money back leads popular consensus to dismiss the film as the product of a bizarre marriage that ultimately serves to nullify the film’s best intentions.

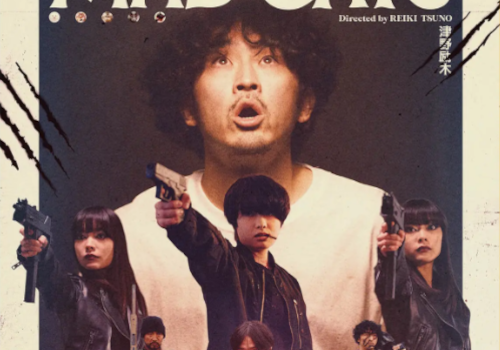

We meet our protagonist, the hulking mountain man Sensaku (played by legend of Japanese wrestling, Keiji Muto), as he reaches Tokyo from his home in Hokkaido, intent on finding his vanished fiancée who came to the city to study. Here he roams the junkyards and dive bars, finding himself stumbling into a subterranean world of modern-day gladiatorial combat that he must explore if he is to ever find his love. In amongst battling people to the death, he meets an opera singer no longer able to sing (Michiru Akiyoshi) and the two begin to roam the city together.

What the book does superbly is positioning the group as a product of their time period, whilst avoiding the great swathes of cliché that have swamped narratives of this era. It clarifies that, as much as punk opened the doors for bedroom Beefheart and Stockhausen obsessives, most of the groups that had any kind of commercial success were still largely in thrall to the glam tentpoles of Bowie and Roxy Music, as well as the tougher end of pub rock. It posits all this whilst articulating clearly how these influences percolated in the surrounding culture of the era, and how this created music that sounded so distant from its core initial influences.

what these bright young directors did lead to was a further interest in the films that inspired them, largely the various European new waves of the late fifties and sixties. It seems to be the origin of this film, which liberally lifts from Georges Franju’s 1960 masterpiece Eyes Without A Face. Make no bones about it, it isn’t a nod, or an homage, it is a straight-up pinch of the whole plot. Well, it is not quite Eyes Without A Face; but it is Face Without The Eyes.

The Dar Es Salaam duo build on their live breakout with one of the best records of the year Sisso is a bulletproof legend of the Singeli scene at this point; his production stands as a core pillar of his label, which formed the backbone of 2018’s Sounds Of Sisso compilation. It was this album that first broke the Dar Es Salaam sound in Europe, and brought its compiler, Nyege Nyege Tapes, into focus as one of the most exciting labels on Earth.

Ozu stands apart. There are few film-makers who command such unanimous acclaim, detractors few and far between, critics as one enraptured by his singular style of delicate, melancholy social satires. This acclaim largely sits upon his post-war films until his death in the early sixties, but his early films remain in need of being seen by a larger audience. It’s a task the BFI has set about with its ongoing blu-ray releases of early Ozu works, and they have chosen two more corkers to focus on this time around.

Well-regarded but under-seen on initial release a decade ago, The Borderlands has become something of a beloved cult favourite, one that along with Ben Wheatley’s early work was key with reviving folk at the centre of horror culture. On its tenth anniversary, this Second Sight re-release gives an opportunity to re-examine the film, and to find it even stronger than the first time round, standing head and shoulders above many of the films that have followed in its footsteps, whilst remaining kind of inimitable, a totally singular concoction.

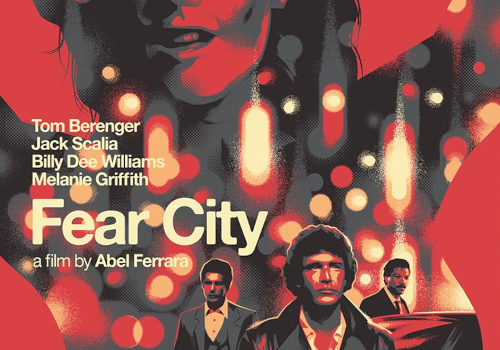

A re-release of Abel Ferrara’s Fear City finds the cult classic as interesting in its flaws as ever. It’s the mid-'80s, New York is pre-clean up, still a landscape of neon, sex and hovering violence. Former Boxer Matt Rossi (Tom Berenger) and his business partner Nicky (Jack Scalia) run a management company for Manhattan’s best strip club dancers.

Nuri Bilge Ceylan maintains an eye for the sublime in hopelessness and vice versa in his latest epic.

I know it’s the oldest trick in the book for distributors to sell their films in as straightforward a way as possible, but Jesus Christ, trying to sell La Chimera as a taut heist film is doing no one any favours. Its only resemblance to The Italian Job is that there’s Italians, and well bugger me they’ve got a job to do. What there is instead, in typical Rohrwacher fashion, a film that defies categorisation, that hovers at the space where divinity meets the reality of a world where greed curdles all corners of life.

It does well to initially evoke its era. The film’s primary tones are garish neon and sweat on skin, like a grimy San Junipero, and the set design and cinematography do well to create sense of a place where macho sleaze permeates every nook and cranny of the town. The problem is the characters that inhabit it feel too archetypal, too lacking in the eccentricities and unpredictabilities that would make them believable.

What we don’t get, thankfully, is simply a The Body album with Dis Fig’s devastating wails atop their usual bludgeoning hellscapes. Instead, their two styles merge symbiotically, folding into each other in a totally seamless way. It makes sense. Both are interesting in creating blown-out, incinerated landscapes of noise, and walking the line between self-flagellation and catharsis.

Following up a breakout film is obviously a difficult position, a constant questioning of whether to continue doing what made you a success in the first place, or to experiment, to use the newfound resources that success affords to embrace grander visions. It’s a position that director Junta Yamaguchi and screenwriter Makoto Ueda find themselves in, and one in which they succeed and fail in equal measure.

This re-release of cult classic Alligator finds it in as joyous as ever; a fun, knowing creature feature wrapped in a lovingly extensive package of remasters and extras from the ever-reliable 101 Films.

The film takes this classic western trope, establishing a small band of characters and setting them off on an expedition, but foregrounds the violence and cruelty at the heart of their quest, with every encounter they stumble upon drawing more and more out of them, and further brutality into the story.

There is something strangely admirable about how big Mad Cats swings, its commitment to its own childish rambunctiousness; but ultimately it can’t string itself together beyond a funny idea and some well-done set pieces. There’s certainly an interesting film-maker in there, and there is evidence of it here; but equally there is one that is still finding their feet, still to nail the difficult execution of a particular brand of absurdity.

Against the backdrop of a 2023 which brought a BFI retrospective, and what looks to be his late career masterpiece, EO, comes this release from Second Run of three of Polish auteur Jerzy Skolimowski’s key early works. They show a truly forward thinking director, whose work from this era remains relatively under-seen compared to his contemporaries, despite it containing some true classics of the European New Wave.