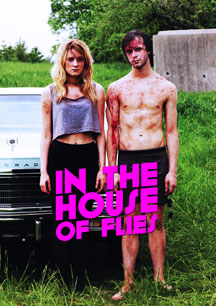

Gabriel Carrer‘s In The House Of Flies is an ’80s movie, made in the second decade of the twenty-first century designed around a trope from the first which became a cliché and eventually a sub-genre all of its own, though it does a bloody good job of avoiding cliché and in the process returns the trope to its ingenious origins.

Gabriel Carrer‘s In The House Of Flies is an ’80s movie, made in the second decade of the twenty-first century designed around a trope from the first which became a cliché and eventually a sub-genre all of its own, though it does a bloody good job of avoiding cliché and in the process returns the trope to its ingenious origins.

In The House Of Flies is so minimal, and so refreshingly unreliant on gore, that it could just as easily work as a radio drama, were it not for the amazing physicality and facial work of its two leads (so the vast majority of the cast, then) Ryan Kotack and Lindsay Smith, who play happy-go-lucky young lovers Steve and Heather, whose lives are changed inexorably when some asshole ruins their holiday by filling their car with chloroform or near equivalent and chucks them in a basement with a phone and a bunch of suitcases. And their chances of coming out to have a heartwarming Netflix sitcom about their readjustment to modern life look minimal, for reasons even greater than Netflix not yet being a thing. To make matters worse, one of them (I’ll let you guess which) is pregnant. At first, of course, they set up a united front against the disembodied voice on the phone that taunts them with threats and challenges, but inevitably cabin fever and starvation rack up the tension between them as the voice plays them off against each other.

In many ways, In The House Of Flies is the exact opposite of Koji Shiraishi‘s notorious Gurotesuku (whose British release, as Grotesque, never happened, because it was the first movie banned outright by the BBFC in 20 years), which used an identical premise to springboard a ludicrously overblown series of physical degradations and mutilations. Here the majority of the torture is either passive (starvation and imprisonment) or psychological, and this is where the movie really comes into its own.The majority of the film consists of conversation, and endless facial shots of the two leads, in a less tropical echo of minimalist shark-attack thriller Open Water, broken by the occasional POV shot as our unnamed villain watches them as they sleep. This tightness of focus is what propels the film — whereas Saw made its plot so convoluted and arcane that there were plenty of holes for its logic to leak out (though to be fair it did a good enough job of hiding them until the action stopped and you had time to think over what you’d just seen), In The House Of Flies sticks rigidly to one inexorable flow of causes and effects, lending a purity to its creepiness.

There’s not a lot of room for a frame-breaking “Why didn’t they do that? That’s what I’d have done” when the characters have no options at all. Sure, it’s nasty, but it’s nasty because being locked in a basement is nasty, rather than because someone’s decided we need to see what fingers look like when they’re cut off. It’s all about tension, backed up by ominous Lynchian bass rumblings, and it’s the kind of movie that stands and falls on the performances of its leads, who are more than up to the job, becoming twitchier and more haunted as the story progresses until it’s as uncomfortable to watch them as it would be to watch the grand guignol excesses of a Saw or a Hostel. Indeed, the most chilling shot in the entire movie is of the telephone, and that’s given all its power by what has gone before between the two prisoners and their captor (who has an air of the Tyler Durdens to him, with his “most people never get to understand themselves the way you are understanding yourself right now” schtick). It’s also not a spoiler, as it’s meaningless without any of that.It’s a movie about cruelty, but isn’t really a cruel movie — there’s nothing gleeful about the way these eminently likeable kids are treated, there’s never a “Oh, hurry up and kill these irritating little shits” moment, such as is common in far too many, more cynical pictures. And because it’s not about gore, you’re never willing the guy on to further visibly invasive bodily procedures just to see what they look like, because that’s not the game Carrer is playing (though don’t get me wrong — some seriously unpleasant things do happen). Instead he’s concentrating on the more interesting questions: what would this feel like? How long could you last without losing your mind? Just how strong are you? And if someone decides to play God and start judging you, how much responsibility do you have for your failings as a human being?

Basically, if you want eyes popping and severed limbs, Eli Roth is your man; he’s a master of that shit. But here in the House Of Flies, Carrer has a subtler, more thought-provoking and ultimately more disturbing fate in store for you.Oh, and that voice on the phone? That’s Henry Rollins, that is.

-Justin Farrington-